The most frequently asked questions have to do with the invention of the chariot. However, the topic is so voluminous it will need three blog segments.

Segment One: Early Chariot History

What is the difference between a chariot and a wagon? Although not always guaranteed to distinguish between them, in the ancient era a wagon hauled cargo and was pulled by oxen, whereas a chariot hauled people and was pulled by horses. Note that the construction of the chariot was not a determining factor. In the oldest representation of a chariot, a chariot from ancient Ur in Sumer had four solid-wood construction wheels.

Its purpose was to carry the king. As such, its primary use was a status symbol. It was not intended for use in battle.

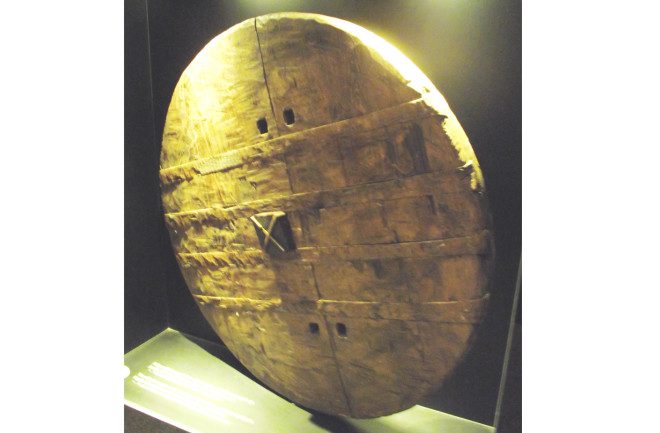

Note: Each of these prehistoric era wheels were three feet or more in diameter – too wide for a crosscut horizontal width of a Middle Eastern tree species. It appear to be an amalgam of three pieces cut vertically from a single tree and assembled by pinning the three sections together by separate strips of wood.

The central problem with the wheel: that era of history lacked the technology to enable them to balance a wheel for high speed. They could only cut the individual wooden sections to an approximate identical thickness. For piecing the three sections together, they could only mate the individual sections to approximately identical patterns and could only position the individual mating crosspieces in an approximately balanced location. The individual pinholes and wooden pins fastening the pieces together were unable to be constructed with precision.

The result: if the chariot attempted to exceed ten miles an hour, the net individual imbalance would shake the chariot to pieces. A man can run faster than that. The result: prehistoric era chariots were not battlefield weapons.

Since chariots were a status symbol, the vast majority of prehistoric era wheeled vehicles were wagons. To haul heavy loads, the vast majority of wheels designs were for strength at slow speeds. That was where the majority of the business was. These wheels were usually two-layers thick. Three or four boards aligned horizontally, while three or four aligned vertically, than all were pinned together. The inner and outer sections were then pinned together back-to-back into one composite wheel and the wheel cut to the desired diameter. That is all most ancient wheelwrights were trained to know. Because only a king and his nobles could afford chariots, wheelwrights with chariot knowledge were as scarce as the chariots they produced.

Segment Two: The Physics-Engineering Problem with Wheels

The core issue with wheels is that they support some form of cart that carries weight. That means that, from the axle down on the “down” side, that weight is compressing the wheel. The problem is that, with no weight on the wheel “up” side, the wheel goes into a rebound mode of expansion. The constant compress-rebound forces cause a wheel to degrade over time. The actual distance the wheel compresses and rebounds is only a few thousandths of an inch, however, the glues that were available in the ancient world were not strong enough to withstand that continuous amount of force. The glues would fail within a few miles.

So, how did they solve the problem?

Think of a bicycle tire today. The wheel has tightened wire spokes so that the whole wheel is under constant tension pulling it in to the center. This tension force is greater than the compression-rebound forces, so that the spoke force dampens and overwhelms them. In ancient times, they fashioned a solid metal tire that wrapped around the outside diameter of the wooden rim. It was installed in a hot expanded condition, then allowed to shrink while cooling. This compressed the wooden rim, overwhelming the compression-rebound forces in the same way bicycle spokes do today.

However, in the days of Abraham, they had not yet invented the technology to make the metal rim the same thickness all the way around the wheel. This meant that there would be an inherent imbalance in metal-rimmed wheels of Abraham’s era.

They needed an interim solution to bridge the gap.

Their solution was to use a leather tire wrapped around the outside wooden rim. The leather was applied while wet, meaning it was in an expanded condition. As it dried, it shrank, holding the wheel in a compressed condition. In addition, they used leather wrappings and ties for other applications on the wheel, but this goes outside the bounds of this discussion.

Have we resolved this issue even today? No. We still have the compression-rebound issue. However, we mask it by using an air-filled tire to mask the effect. We still can’t make a tire that is continuously the same all the way around. However, we compensate for it by “balancing” car tires with weights on the metal rim. The tires still degrade with wear over time. However, we extend their life by periodically “aligning” them. We have improved today’s tires by extending their mileage from fifty to fifty thousand miles or more between replacement. But today’s tires still wear out.

Segment Three: Abraham Era Chariot

I need to make a disclaimer. There is insufficient data to know even approximate dates several chariot “improvements” were applied which transitioned chariots from the Sumer to the Rameses II era chariots depicted in movies. Why? Differing peoples in differing areas of the world made individual changes, none of who documented information of this type. In addition, there have been insufficient archeological remains recovered to have an accurate timeline. The information just is not there.

Therefore, I needed to make assumptions. These largely mirror what archaeologists report as their “most likely scenario,” however, remember that no one knows for sure. I ask for your indulgence to accept these decisions for the story’s benefit.

The first and most important change was to ditch the solid wheel. For over a thousand years, the even thickness imbalance problem lacked a solution. They needed to “reinvent” the wheel. They went to a composite wheel: axle, spokes and rim.

The constraining factor was the rim. They had not yet invented the ability to bend a wooden beam into a 360 degree form, so they depended on a single horizontal cut across a tree trunk. Their available wood sources limited that to a two-foot diameter. That limited the number of spokes to four. There simply was no room for more.

They now had an invention that had enough stability to enable the horses to pull it at a gallop. However, there remained serious drawbacks. The small diameter required the axel to be a foot off the ground, so any significant-sized rocks or obstacles could affect the chariot, even to breaking the axle. In addition, with the cab riding directly on the axle, any uneven ground would transfer shock to the carriage, affecting an arrow’s aim.

But – it worked. Well enough for the Hyksos, who probably used the Mitanni kingdom’s four-spoke chariots, to conquer Egypt in 1645 BCE +/- five years.